Pattern Sequencing

The earliest analog synthesizers required you to connect different modules — oscillators, envelope generators, LFOs, filters — using patch cords. (Looking at a Moog modular synthesizer will give you an appreciation of the patch cord “spaghetti” that resulted.) Some of the patch cords carried audio signals, such as the ones connecting the outputs of oscillators to the inputs of filters. Other cords carried control voltage signals. These signals were not meant to be heard; rather, they were used to control parameters like oscillator frequency or filter cutoff.

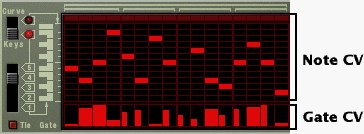

Reason preserves some of this way of doing things, with its audio patch cords and flexible modulation features. Sections within a synthesizer — like the LFO section in SubTractor — can control another section within the same synthesizer. And, of course, patch cords route audio signals between devices. But Reason takes the analogy to analog synthesizers further by providing various CV (control voltage) connections on the back of the rack. A CV connection lets one device control some aspect of another device.

Some analog synthesizers had step sequencers, which generated a repetitive sequence of control voltages, some with as many as 256 steps. Each step stored a voltage that the user could adjust with a knob. The steps were of equal duration, and the user could change the tempo. At each step, the sequencer would emit the stored control voltage, which could be routed to control most anything, such as oscillator frequency, amplitude, filter parameters, etc. When the sequencer performed the last step, it would start the sequence over from the beginning. You can hear a step sequencer at work in the Pink Floyd song, “On the run,” played on an EMS Synthi AKS synthesizer.

Reason has a step sequencer, called the Matrix Pattern Sequencer, which can store 32 different patterns (or sequences of steps). In this part of the assignment, we’ll learn how to control SubTractor with this sequencer. Of course, the Redrum drum machine also has a step sequencer.